- Academic paper claims methane emissions in gas production chain wipe out GHG advantage of LNG over coal

- Paper assumes methane leaks in gas production stand at 2.6% of total output, diverging from majority of opinion

- Producers with old infrastructure worst methane emitters compared to modern technology users, other study shows

- Momentum gathers to tackle methane emissions in upstream after announcements by US, EU and at COP28

Last week’s decision by the White House to pause pending and future applications to export LNG to non-FTA countries, citing the need to reassess the economic and environmental impact of LNG exports, once again highlighted the issue of methane emissions in the LNG supply chain – often referred to as the industry’s ‘Achilles heel’.

Reporting on the 26 January announcement, news outlets – including the UK’s Guardian – cited claims made last year by a prominent academic that, when all factors are taken into account, LNG is no cleaner in terms of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than coal. If so, this would undermine the whole basis of a strong role for LNG in the energy transition.

Closer examination reveals that this claim is based on pessimistic assumptions on how much methane is leaked from upstream oil and gas operations. However, the fact that this possibility can be mooted at all is testimony to the importance of tackling methane emissions, which a series of major announcements made in recent months suggest is gathering momentum.

‘Top-down’ vs ‘bottom-up’

The credentials of natural gas as a transition fuel are largely predicated on the hypothesis that, while natural gas has a higher GHG footprint than renewable energy sources, it is a lot cleaner in this respect than coal, and that coal-to-gas switching, particularly when there is existing gas-fired generation that can run at a higher capacity factor, is a practical way to rapidly reduce emissions.

Advocates of natural gas can point to the fact that some of the biggest ‘wins’ in reducing CO2 emissions have been from coal substituting for natural gas – most notably in the US as a result of the shale gas revolution, but also in the UK as a result of the policy-induced move away from coal.

Against this backdrop, The New Yorker published an article on 31 October 2023 subtitled “A new analysis suggests that LNG exports may well be worse for the environment than burning coal”. The article’s source was an October 2023 paper[i] by Dr Michael Howarth of Cornell University published as a pre-print, meaning, not yet subject to the peer review process. In this paper, Howarth carries out a life cycle analysis (LCA) of the GHG emissions from US LNG exports, from exploration and production of natural gas through pipeline transport, liquefaction, shipping, regas and in-country distribution and end-use.

Howarth’s conclusions – in essence, that the methane emissions involved in the production chain more than wipe out any GHG advantage gas has over coal – are startling. In all the scenarios he has considered, he finds that the methane emissions, primarily from upstream production, are actually greater in terms of global warming impact than the CO2 from the end-use combustion of the gas. Moreover, the life cycle emissions from the full wellhead-to-burner tip LNG chain are between 24% and 274% higher than in a comparable chain for coal, Howarth adds.

READ US pause on LNG projects adds new dimension to negotiations with buyers

This is not the first time that Howarth has come up with analyses that shed doubt on the environmental credentials of gas and LNG based on the negative impacts of methane emissions. In 2021 he published an analysis which he said showed that the GHG emissions from burning blue hydrogen would actually be higher than those from burning natural gas itself, thus defeating the object.

Howarth’s LNG analysis seems at odds with other peer-reviewed analyses, such as a 2021 article published by the American Chemical Society (ACS). His previous work has attracted strong criticism, particularly from industry groups.

Even without going into the details of Howarth’s analysis, where he diverges most from the majority of industry opinion is clear: he assumes that methane leaks from natural gas production amount to 2.6% of the total output. He bases this figure on data from a range of so-called ‘top-down’ studies that involve measurements of methane emissions by plane or satellite sensing actual methane plumes in the air above gas production locations.

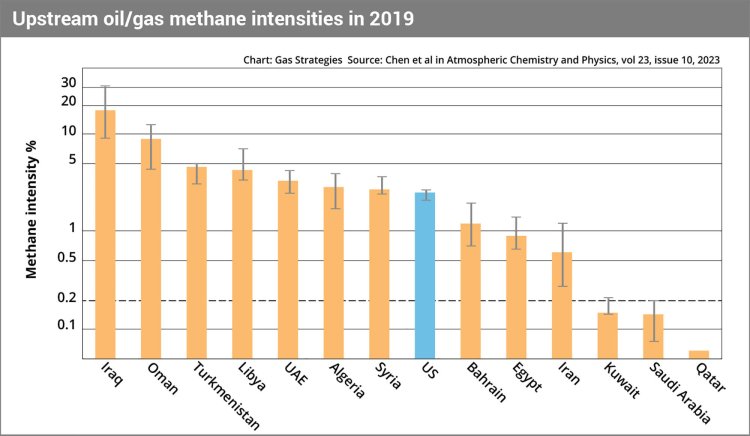

The top-down approach, which aims to measure methane emissions directly, contrasts with ‘bottom-up’ measurements typically based on engineering estimates of equipment performance. The problem with the bottom-up measurements is that they have tended to estimate emissions under ‘normal’ operating conditions and often do not include accidental leaks and effects of poor operating standards. The impact of these factors is shown by studies which suggest a huge difference in methane emissions intensity – i.e. methane emissions as a percentage of natural gas production – between countries.

The spread of these intensities is striking – and also instructive. Some of the worst emitters are countries like Iraq, Turkmenistan and Libya, which have old, widely dispersed infrastructure, and where one would suspect maintenance and operational standards may not be of the highest. The prevalence of gas flaring also has an impact: though flaring should in principle eliminate methane and convert it to CO2, flares are in fact often inefficient and a lot of unburnt methane escapes to the atmosphere.

At the other end of the methane intensity scale, with very low measured emissions, are Saudi Arabia and Qatar, with modern facilities concentrated in large production sites.

The US comes out somewhere in the middle of the pack in this analysis, with a methane emissions intensity of around 2%, roughly consistent with what Howarth uses. It is, however, considerably lower than what industry sources use. The ACS’ 2021 LCA analysis that was based on information supplied by Cheniere used a methane intensity of 0.65%, for example. The two numbers are not necessarily inconsistent. There is likely to be a big range in emissions from different operators, reflecting different operating practices.

A gas buyer like Cheniere, which is a member of Oil and Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP) 2.0, the United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) flagship oil and gas methane emissions reporting and mitigation initiative, and supplies ‘tags’ for all its cargoes indicating the emissions associated with their production, is likely to source gas from suppliers that are at the lower end of that range. Naturally, sceptics and oil and gas industry opponents will have other explanations of the apparent discrepancies. For example, Greenpeace has castigated Cheniere’s emissions tagging as being based on a “misleading” methane analysis.

CO2 equivalents

It is not only the methane emissions intensity where there is a big difference between the numbers that Howarth has used and industry data. Industry sources usually quote emissions data in terms of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2(e)) measured over 100 years. Howarth uses 20 years arguing this is a more relevant time period. This makes a more than 250% difference in the assessed emissions in terms of CO2 equivalents.

The question of what time period to assess the GWP over is a moot point. In terms of the total impact on climate over the long term the 100 year assessment is justifiable. But if one believes that the short term impact is more important because the climate may be pushed to tipping points, then the 20-year figure would seem appropriate.

In pragmatic terms, the exact level of methane emissions may not be that relevant – the point is that oil and gas operations do not actually need to emit large quantities of methane at all. A significant amount of the emissions seem to come from poor operating procedures and old facilities. Some of it also comes from operating procedures that were developed back when methane emissions really did not matter. As the satellite data for Saudi Arabia and Qatar have shown, efficient operations do not leak methane.

The global-warming potential of methane

There are two key parameters that differentiate the global-warming potential (GWP) of different gases in the atmosphere. The first is the amount of energy they absorb and the second is how long they are present in the atmosphere. The reference is carbon dioxide, which has a half-life in the atmosphere of over 100 years. Methane is a much more potent absorber than CO2, but is relatively short lived, with a half-life of around 10 years.

Compared on a 20 year basis, methane has 84-87 times the GWP of the same mass of CO2 according to the IPCC. However, after 20 years the methane has largely disappeared, having been converted to the corresponding quantity of CO2. As a result, measured over a very long period – usually 100 years – the GWP of methane is much less – in the range 28-36 times that of CO2.

Methane regulations

In the light of the growing mass of data on emissions and of the role of methane in global warming, it is not surprising that efforts to contain methane emissions are on everyone’s agenda, especially in the light of worrying signs of major increases in recent years in the concentration of methane in the atmosphere, which is now around two and a half times pre-industrial levels. Since the middle of last year, there has been a plethora of announcements on methane.

In the run-up to COP28 in Dubai, the EU announced that it was planning to move ahead with legislation which would put a limit on the methane emissions intensity of imports. At the COP meeting itself, a group of oil and gas producers representing some 40% of global oil production signed up to the Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter (OGDC). In it, the signatories commit, among other things, to net-zero operations by 2050 at the latest, to end routine flaring by 2030, and to achieve near-zero upstream methane emissions.

READ EU Methane Regulations: Here’s what you need to know

On the same day that the OGDC deal was announced, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) came out with new regulation on methane which the administration claims gives the US the most protective methane regulations of any country. The new regulations will impose emissions standards and monitoring procedures aimed at identifying and significantly reducing, if not eliminating, routine emission of methane.

The EPA regulations have attracted praise from environmentalists and some industry players. Orlando Alvarez, the head of BP America, said that “BP welcomes the finalization of a federal methane rule for new, modified, and – for the first time – existing sources.”

Smaller, independent US producers have reacted negatively, fearing for the consequences of the new rules on their livelihoods. Jeff Eshelman, the president of the Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPPA) criticised what he called “the EPA’s overbearing regulatory regime” and estimated “that EPA’s recently finalized methane rules will lead to the shutdown of 300,000 of the nation’s 750,000 low production wells”.

Icing on the cake

In contrast to the seemingly intractable discussions on how CO2 emissions will be reduced, legislators and operators seem to have discovered that tackling methane emissions can be done through clear technical steps everyone can agree on – albeit with some pushback from some of the more recalcitrant oil and gas companies.

Pushback from some quarters on stricter methane regulations is, of course inevitable. Equally inevitable is that some environmentalists will not give credence to industry pledges to eliminate methane emissions. But there are good reasons to prioritise efforts to reduce methane emissions. The technology to all but eliminate methane emissions is very accessible, and poses fewer challenges than does elimination of CO2 emissions. What is more, because of the relatively short lifetime of methane in the atmosphere, if leaks are fixed, time will wipe the slate clean relatively quickly and the past emissions will be gone, which is not the case for CO2. And, as icing on the cake, a significant proportion of the current methane emissions can be fixed at no net cost, as the gas saved can be monetised.

All this makes tackling oil and gas industry methane emissions a low-hanging fruit in the efforts to reduce GHG emissions. Success in this area would certainly be the best, and definitive, response to accusations that LNG is a higher emitting fuel than coal. - DJD

Subscription Benefits

Our three titles – LNG Business Review, Gas Matters and Gas Matters Today – tackle the biggest questions on global developments and major industry trends through a mixture of news, profiles and analysis.

LNG Business Review

LNG Business Review seeks to discover new truths about today’s LNG industry. It strives to widen market players’ scope of reference by actively engaging with events, offering new perspectives while challenging existing ones, and never shying away from being a platform for debate.

Gas Matters

Gas Matters digs deep into the stories of today, keeping the challenges of tomorrow in its sights. Weekly features and interviews, informed by unrivalled in-house expertise, offer a fresh perspective on events as well as thoughtful, intelligent analysis that dares to challenge the status quo.

Gas Matters Today

Gas Matters Today cuts through the bluster of online news and views to offer trustworthy, informed perspectives on major events shaping the gas and LNG industries. This daily news service provides unparalleled insight by drawing on the collective knowledge of in-house reporters, specialist contributors and extensive archive to go beyond the headlines, making it essential reading for gas industry professionals.